Enter the Wildness: The Fantastical World of Susan Jamison Essay

Susan Jamison: Super Natural exhibition catalogue, perfect bound, 2016.

Published by Longwood University Center for the Visual Arts.

The paintings and installations of Virginia-based multi-media artist Susan Jamison celebrate myths and dreams in tangible ways. Referring to her work as “uniquely feminine,” Jamison slyly suggests a greater narrative of our collective relationship to nature but through a gender-centric lens. The female form is always present—in obvious as well as subtle ways—in her work. An avatar for Jamison, the figure also serves the function of an archetypal woman, a universal “everywoman.”

Growing up, Jamison spent her summers in the wooded hills of southern Indiana near the Kentucky border and was given free rein to explore nature and all its inhabitants. Wearing homemade dresses sewn by her mother, Jamison re-envisioned fairy tales in the deep forest as well as exploring the secret feminine stories passed down from her mother and grandmother. These experiences of wildness made a large impact on Jamison and were the catalyst for her to create mysteriously symbolic paintings and installations that investigate the universal woman as soothsayer, creator, lover, giver, warrior, and temptress. In the exhibition “Super Natural,” at the Longwood Center for the Visual Arts, Jamison brings her wildness full circle and presents her egg tempera paintings with a new multi-media installation titled “Feathers and Weights.”

Subject matter for her paintings comes from Jamison’s visions. Deliberately using loaded yet familiar imagery as a way to create an entry point for the viewer, she paints in egg tempera, a medium with beginnings in early Egypt. Notoriously fussy but very durable, the technique is fast drying, with pigment intermingled with egg used as a binder. Her chosen medium allows her to render her subjects in delicate brushstrokes; each deliberate mark is visible on the surface. To create her paintings, she starts with a drawing on tracing paper, which she then transfers to a hardboard panel and then paints. Harkening to Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli and Baroque painter Givanna Garzoni, Jamison’s subjects demand our attention with the hyper-realistic and lush detail afforded them, giving the illusion that her creatures—flora and fauna alike— are alive.

Jamison’s women are not the milk-toast pale lovelies cherished by the male artists of the Pre-Raphaelite art movement but strong warriors, often embellished with body decorations, and accompanied by Naguals (spirit animals), who act as protagonists in her paintings. Her Naguals are messengers, often bearing and/or leaving enigmatic words or phrases worked into unexpected materials such as lace and spider webs. In her painting “Trust in Me” (2007), a snowy owl is captured in mid-flight; in its talons is a lace tatted message that it transports to the female figure’s outreached hand. The woman and the owl are luminescent and hover over the rich velvety black background that highlights their complex and mysterious connection.

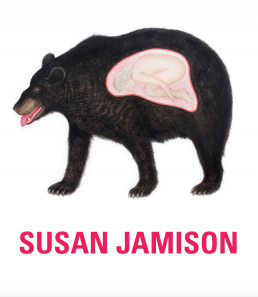

Often in Jamison’s paintings, references to work historically assigned to women such as sewing, embroidery, spinning, and weaving are interwoven with the activities of woodland creatures who act as helpmates. In her spider web paintings, “See Me” (2016), “Note to Self” (2015), and “Destroy Me” (2016), delicate webs outline loaded prompts to the visitor. Jamison envisions them as messages to a “grown-up fern by the barn spider Charlotte A. Cavatica” in E. B. White’s children’s book “Charlotte’s Web.” The artist comments, what advice would Charlotte have imparted to the adult fern regarding her genesis as a woman? “In Repair Me” (2006), a cluster of delicate red-throated hummingbirds hover in midair holding a red thread to repair the female figure’s embellished arm while her hand has just dropped a crimson rose. Hinting at a greater narrative not visible to the viewer, the depiction makes us wonder if the woman has dropped the crimson rose as a signifier of a lost love. Like the animals in “Charlotte’s Web,” Jamison’s embody core humanistic qualities. In “Power Bear” (2013), a large bear carries a woman in her womb. The recumbent woman is safe and nourished while the bear acts in the role of mother. Presenting an act of gestation rendered in egg tempera brings Jamison’s interest as in “nature as a subject matter and medium” full circle.

In conjunction with her paintings, Jamison has focused on an alternative body of work that employs objects with meaningful history to create statements about women’s work: how women process loss or receive wisdom. In that vein and at the core of the exhibition is a new site-specific installation titled “Feathers and Weights.” In the center of the gallery, the viewer encounters a nine-foot-round circle made with sifted red clay harvested from Southwestern Virginia. Placed at intervals on the circle are twelve objects that represent an enigmatic ritual, from a bundle of horse hair and a delicate cup engraved with the word “Mother” to sea salt, a cotton cord with nine knots, sage, and a brain-like shape made from cotton roving among other totemic objects. In the center of the circle is the silhouette of a woman made from powdered marble, its shape based on the artist’s body. Hovering above the figure is a white owl formed from silk organza. The owl symbolizes Athena, the greek goddess of wisdom and courage. The owl and figure are tethered together by red cotton floss, weighted with heavy teardrop metal lures. Alluding to an ancient divining ritual invented by humans centuries ago to give comfort and reassurance over their everyday hardships, Jamison’s ritual is one of wisdom and nourishment for the archetypal woman. Jamison’s ritual provides hope to “feed” her and by proxy, ourselves. By inserting her body in the ritual, Jamison joins a long daisy chain of artists who implant their own forms in the land such as Cuban performance artist Ana Mendieta. Like Mendieta’s work, Jamison’s installation “Feathers and Weights” is autobiographical and yet universal, while being harnessed firmly to nature. Jamison leaves it up to the viewer to complete the circle and perform the ritual.

Susan Jamison is firmly placed in the art historical canon with other artists such as Kiki Smith and Louise Joséphine Bourgeois. All created work that challenged preconceived notions such as fear, death, desire, love, and the fleeting nature of beauty. Jamison’s work in “Super Natural” takes it a step further by displaying universal narratives of the “everywoman” role in nature. Guided by her spirit animals, Jamison’s archetypal woman navigates her way through the joys and pitfalls of love and loss while gaining knowledge and strength along the way. Her installation in the exhibition is the culmination of Jamison’s powerful work, with each flanking painting providing valuable clues to its mythical and magical prescribed actions. Unlike the traditional portrayals of women in many fairy tales, Jamison’s woman is noble, a heroine in control of both her actions and her destiny.

Amy G. Moorefield, Deputy Director of Exhibitions and Collections

Taubman Museum of Art